Stigma: The Preventable Barrier to Mental Health Care

Rebecca Wheeler – MA, MEd, CSAPC

For people with mental health and substance use disorders, stigma is often a roadblock to treatment. A 2012 CDC report defines stigma as “negative attitudes and beliefs that motivate the general public to fear, reject, avoid, and discriminate against people with mental illness.” Three aspects of stigma: social isolation, self-stigma, and discrimination, decrease a person’s likelihood of seeking treatment. Stigma also reduces the public’s will to provide and legislate funding for mental health services. Even if services do exist, people may perceive a lack of services and thus not seek treatment.

The World Health Organization names mental health issues as the world’s “biggest economic burden,” costing nations $2.5 trillion in 2010 and an estimated $6 trillion by 2030 (Friedman 2014). Two-thirds of that cost is attributed to disability and a loss of work. In any given year, 26.2% of adults 18 and older experience a mental health disorder, but only 35% seek professional help (Friedman 2014). The outlook for young adults is bleaker, as only 18-34% seek help for a major depressive episode (Friedman 2014). Mental illness is common and can happen to anyone. Fighting stigma must be recognized as an important strategy for preventing negative outcomes for those with mental health and substance use disorders.

Social Isolation

Persons with mental health and substance use disorders often experience social isolation. From childhood, kids are taught to use words like “crazy” and “weird” to describe others whose behaviors are not considered the norm (Friedman 2014). Many adults perceive those with mental illness are dangerous; ideas often fueled by negative media and the idea that violent criminals are mentally ill (Friedman 2014). Fear increases social isolation as people avoid interacting with those labeled as “dangerous.” Even healthcare professionals might harbor these biases, which impacts care.

Persons with mental illness may socially isolate themselves to avoid embarrassment or disclosure. Some might believe that they should be able to handle problems without asking for help or have negative attitudes toward seeking help (Gulliver, et al. 2010). One review of 22 studies showed that stigma and embarrassment were the primary reasons for not seeking help (Friedman 2014). Such isolation tends to decrease a person’s sense of self-efficacy and decrease recovery outcomes.

Self-Stigma

Self-stigma is ‘felt’ even when discrimination is not present (Centers 2012). “People’s beliefs and attitudes toward mental illness also frame how they experience and express their own emotional problems and psychological distress and whether they disclose these symptoms and seek care,” (Centers 2012). People who already believe that those with mental illness are dangerous and burdens are more likely to internalize those stigmas when they experience their own personal mental health concerns (Watson, et al. 2007). People might avoid disclosing symptoms and adopt unhealthy behaviors to cope, such as substance misuse and eating disorders (Centers 2012). To avoid seeking help, people may alter “the meaning they attach to this distress, and in particular whether or not it is ‘normal’ in order to accommodate higher levels of distress and avoid seeking help” (Gulliver, et al. 2010). In other words, the person knows he or she is under distress, but justifies his or her feelings as ‘normal’, and determines professional help isn’t necessary.

Discrimination and Accessibility

Negative stereotypes may lead to discrimination and a lack of mental health treatment services. Stigma results in lower prioritization of public resources for mental health services. “People’s beliefs and attitudes toward mental illness set the stage for how they interact with, provide opportunities for, and help support a person with mental illness,” (Centers 2012). A 2012 study reported that the public was less willing to pay for prevention of mental illness than physical illness (Centers 2012). Surveys show the general public’s understanding of the biological causes of mental illness have improved; however, this understanding appears unrelated to improving negative perceptions (Centers 2012). In some cases, learning about biological causes increased negative perceptions of mental illness (Centers 2012). The biological knowledge “proved” that persons with mental illness are dangerous thus increased social isolation. Personal biases must be confronted when educating people with the facts.

According to a CDC report, over 80% of respondents felt that treatments for mental illness were effective, but only 35-67% felt people were sympathetic toward those with mental illnesses (Centers 2012). Persons with mental illness were even less likely to agree that the public was sympathetic. People in states with increased mental health services were the most likely to say treatment is effective and that people are sympathetic (Centers 2012). Accessibility to treatment not only improves health outcomes, but also decreases stigma.

People living in rural populations have greater concerns about accessibility to mental health services, and rightly so, as urban centers tend to have increased concentrations of mental health resources (Gulliver, et al. 2010). Additional barriers include a lack of transportation and high costs associated with care.

In a study of young adults, the perceived “quality” of school-based providers impacted whether or not youth asked for help. Youth reported concerns about confidentiality and fears counselors would overreact. Additionally, youth reported being uncomfortable talking to someone about mental health who also must enforce school rules. (Gulliver, et al. 2010)

Action Steps to Minimize Stigma

1. Make efforts to minimize personal bias. Engage in trainings that help to identify and manage your own bias toward mental illness (Friedman 2014).

2. Improve mental health literacy for youth and adults. Mental health literacy includes the “knowledge and beliefs that can aid in the recognition, management, or prevention of mental health disorders,” (Centers 2012).

3. Improve young adult mental health support. Build the emotional competence of young adults, promote a positive attitude about seeking help, and address the youth’s desire for self-reliance. Emotionally supporting a young person will increase a willingness to disclose when they need help (Gulliver, et al. 2010).

4. Encourage opportunities to engage in support groups. Identifying with a group of people who’ve had similar experiences increases self-esteem, reduces self-stigma, and helps individuals to know they are not alone. (Watson, et al. 2007)

References:

Friedman, M., PhD. (2014, May 13). The Stigma of Mental Illness Is Making Us Sicker.

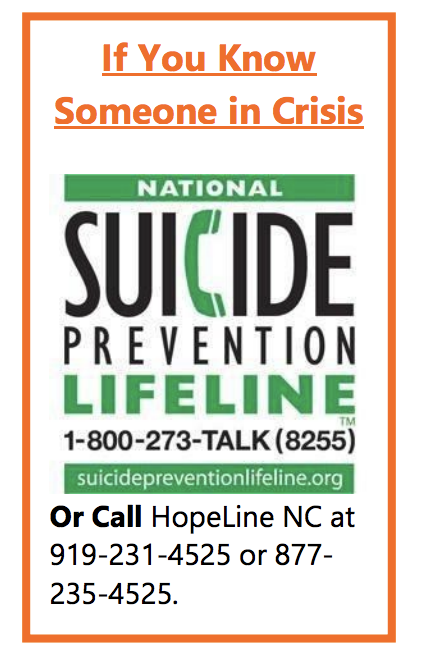

5 Action Steps for Helping Someone in Emotional Pain

1. Ask: “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” It’s not an easy question but studies show that asking at-risk individuals if they are suicidal does not increase suicides or suicidal thoughts.

2. Keep them safe: Reducing a suicidal person’s access to highly lethal items or places is an important part of suicide prevention. While this is not always easy, asking if the at-risk person has a plan and removing or disabling the lethal means can make a difference.

3. Be there: Listen carefully and learn what the individual is thinking and feeling. Findings suggest acknowledging and talking about suicide may in fact reduce rather than increase suicidal thoughts.

4. Help them connect: Save the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s number in your phone so it’s there when you need it: 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You can also help make a connection with a trusted individual like a family member, friend, spiritual advisor, or mental health professional.

5. Stay Connected: Staying in touch after a crisis or after being discharged from care can make a difference. Studies have shown the number of suicide deaths goes down when someone follows up with the at-risk person (e.g. phone calls, etc.).

Additional Resources on Organizational Suicide Prevention Best Practices

http://www.togethertolive.ca/policies-and-protocols

http://www.togethertolive.ca/best-practices-risk-management

See a complete list of resources here.

Featured Poe Program: Youth Mental Health Training

Featured Poe Program: Youth Mental Health Training

Grade Level: Adults

Program Length: September 26th, 2018 | 8 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. | Poe Center for Health Education

Youth Mental Health First Aid is designed to teach parents, family members, caregivers, teachers, school staff, peers, neighbors, health and human services workers, and other caring citizens how to help a adolescent (age 12-18) who is  experiencing a mental health or addictions challenge or is in crisis. Youth Mental Health First Aid is primarily designed for adults who regularly interact with young people. The course introduces common mental health challenges for youth, reviews typical adolescent development, and teaches a 5-step action plan for how to help young people in both crisis and non-crisis situations. Topics covered include anxiety, depression, substance use, disorders in which psychosis may occur, disruptive behavior disorders (including AD/HD), and eating disorders.

experiencing a mental health or addictions challenge or is in crisis. Youth Mental Health First Aid is primarily designed for adults who regularly interact with young people. The course introduces common mental health challenges for youth, reviews typical adolescent development, and teaches a 5-step action plan for how to help young people in both crisis and non-crisis situations. Topics covered include anxiety, depression, substance use, disorders in which psychosis may occur, disruptive behavior disorders (including AD/HD), and eating disorders.

Register here for this one-time session or search for similar trainings here.

Learn more about our Annual Meeting & Luncheon Conferences here.